Dartmouth Alumni Magazine

January/February 2023

Dartmouth was one of the first centers of higher learning I ever heard about: Soon after my family moved to California, from gray and dusty Oxford, England, my first babysitter, Nick, turned out to be a proud recent graduate who wowed me by saying he'd played quarterback for the football team. Later, by pure coincidence, he would become my seventh grade teacher and a cherished mentor who remains, 60 years on, a great friend of my family and of his beloved alma mater. And long before I had digested that Shonda Rhimes '91, Mindy Kaling '01, and Louise Erdrich '76 had all passed through its halls, I bowed before the College with respect because my unparalleled friend and colleague, war photographer James Nachtwey '70, whom I see as one of the great heroes of conscience and courage of our times, not only studied there but, after almost half a century of crisscrossing the globe covering affliction, remains so devoted to it.

Nothing, however, prepared me for the simple, complex joy of stepping off the Dartmouth Coach on a warm Sunday evening in early October—the sky a flood of brilliant colors against a roseate background after the murk and congestion of Boston—to be greeted by the sugar maples blazing red and gold on the Green right outside my window. This wasn't complete chance: As soon as professor Steve Swayne told me, in 2019, that I was to be a Montgomery fellow—thanks to the support of the brilliant and multi-talented anthropologist Sienna Craig—we agreed that I should come when the leaves were at their finest, if only so I could compare the New England fall with the resplendent Japanese autumn I'd chronicled in a recent book. My stay for October 2020 got postponed due to Covid-19 and postponed again, but we agreed not to make my visit virtual, not to reschedule it for spring. If April is the cruelest month, as T.S. Eliot wrote, October in New Hampshire is surely the most munificent.

Having served time, for seven years, at Oxford and at a university down the road in Cambridge, Massachusetts, that shall go unmentioned—and having recently taught at Princeton—I thought I'd met my share of bright students. But again and again I was taken aback by the freshness, the engagement—the diversity—of the people I met at Dartmouth. There was the half-Bulgarian freshman, educated in an Omani town known for its camel market, who told me casually about learning Latin and Greek in Massachusetts (he now speaks Japanese far better than I, though I've lived in Japan for 35 years); the shining young sophomore of Turkish descent who had thought so much and so deeply on life that she was delivering sentences I had only begun to intuit at the age of 50; the young poet from Kenya who asked me, softly, how we might be able to incorporate silence into our work.

My first event was a lunch with graduate students, and every single one of the fascinating and open-hearted people I met (from Serbia, from China, from Nepal) turned out to be a scientist, eager for some reason to meet a literature major who can barely tell chemistry from physics. At a dinner for School House, a huge group of engineering and management students from every corner of South Asia showed up to engage me in discussion of life and love deep into the night, together with a freshman and sophomore who humbled me with their commitment to Buddhist meditation. In a class on attention, I got to listen to Russian poets speak on the liberation of going unplugged, an undergraduate talk of how the lemon trees looked when she was in love; in a class on memory, I had to address a young woman's penetrating question on how permanence and impermanence dance together in any relationship.

When I had breakfast one bright morning with my fellow Montgomery fellow, professor David Silbersweig '82 of Harvard, we grew so excited talking—about a temple-filled mountain in Japan, our talks with the Dalai Lama, the haiku poet Bashō, how words can be used for healing—that we had to carry our conversation all the way from the Hanover Inn to Montgomery House and then, later in the day, extend it in Spaulding Auditorium. I expect a neuroscientist and psychiatrist to tell me a lot about the brain, but now I was learning about music and Japanese woodblock painting and the philosophy in which my new friend had majored, about spirit and heart.

As much as anything, I was moved by the rare sense of affection I felt between the students and their College. I confess to few feelings of fondness for the fine universities where I studied, but everywhere I turned in Hanover, I ran into alumni who chose to return to help or to celebrate the College that would always remain central to their lives. One morning I had tea with a plein air watercolorist from Seattle who had flown all the way across the country in part to transcribe the colors of the fall in the beautiful town where he had studied 15 years before.

It's common, I'm sure, for visitors to rave about the Orozco murals (I visited twice), the cozy sunlit reading spaces in the library in Sanborn, the walk around Occom Pond, the Turkish tiles in the Hood Museum. But it's the intangibles—the faculty members who have stayed here, delightedly, for 40 years or more, the list on the Hanover Inn board of all currently returning graduates, the way a professor, with great sincerity, quoted to me lines from the Dartmouth alma mater—that will stay with me as I fly back across the ocean to Japan.

I'm not 100-percent convinced that the autumn here really is more spectacular than in the thousand-year-old capitals known as Kyoto and Nara, where every maple and gingko has been laid out for maximal aesthetic effect. But I found so much at Dartmouth that I've never experienced in 48 years of constant travel. Perhaps the highlight of my trip came when, near the end of my stay, Professor Swayne invited me to come back for an even longer visit a couple of years from now, perhaps so that I could see that the autumn at Dartmouth has depths—and lessons—I could never find elsewhere, not even in my beloved Japan.

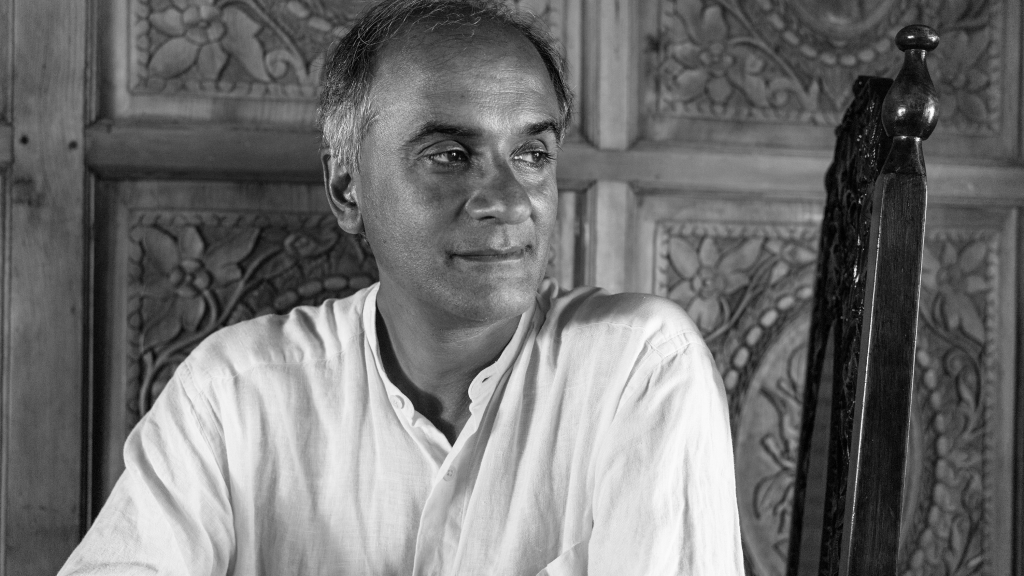

Pico Iyer was a Montgomery fellow in the fall of 2022. He is the author of 17 books, translated into 23 languages, including the forthcoming The Half Known Life.