Author and New Yorker Writer Philip Gourevitch Visits Dartmouth as Montgomery Fellow

Award-winning author Philip Gourevitch will talk about his work in a public lecture, “Crime Scenes and Aftermaths: Writing About Wrongs and Reckoning with Survival,” on July 17.

Gourevitch, a staff writer for The New Yorker, is in residence summer term as a Montgomery Fellow through July 19. His lecture begins at 4:30 p.m., in Filene Auditorium, located in Moore Hall.

Gourevitch has written three books: Standard Operating Procedure, the comprehensive story of Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison and the prisoner abuse committed there by American soldiers; A Cold Case, about a New York Police Department officer’s dogged investigation of a nearly 30-year-old unsolved double-murder case; and We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families: Stories from Rwanda, his account of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, in which 800,000 Tutsis were killed in 100 days by the majority Hutu group. Gourevitch won several awards for the latter, including the National Book Critics Circle Award.

gourevitch-590.jpg

Philip Gourevitch, an award-winning author and staff writer for The New Yorker, will deliver his Montgomery Fellow lecture on Tuesday, July 19, at 4:30 p.m. in Filene Auditorium. (photo by Bonnie Barber)

During his residency, Gourevitch will meet with students and faculty, and speak to students in Government Professor Simon Chauchard’s “Ethnic Politics" class and Anthropology Professor Nathaniel Dominy’s “Lemurs, Monkeys, Apes” class.

Gourevitch lives in Brooklyn, N.Y., with his wife Larissa MacFarquhar, also a writer for The New Yorker, and their two children.

He spoke earlier this week with Dartmouth Now—shortly after arriving in Hanover from Rwanda—about writing, journalists as activists, and about Rwanda.

Here’s an excerpt of the interview:

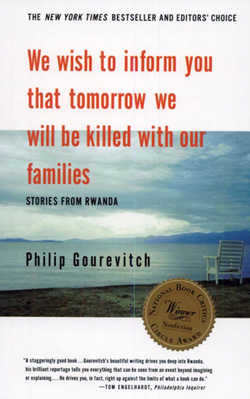

gourevitch_book-250.jpg

Gourevitch’s 1998 book about the aftermath of genocide in Rwanda won the National Book Critics Circle Award and is taught in many colleges and universities.

On becoming a writer: The best and only real education a writer can have is reading. Read anything and everything that you’re drawn to. And it’s good to read both for writing and for plot. Of course you’ll read the 20th century greats, but you should also read contemporary writers. I read and I think everyone should be reading lots of Virginia Woolf, [Norman] Mailer, Marilynne Robinson and Philip Roth, Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, Huck Finn and Moby Dick. Work on understanding how people are writing and why certain kinds of stories and things excite you. The biggest risk young writers have is that either they have a defining story that exceeds their ability to write. Or much more often they develop technical chops—they learn how to write good sentences, they understand the structure of writing—before they’ve figured out what they might have to say or how they want to say it.

Journalists as activists: [The New York Times’ Nicholas] Kristof has a very specific idea of what he means by wanting readers to pay attention. He means that paying attention should always translate into taking action. And that one should presume that a bunch of newspaper readers, if they were paying attention, would take action and would solve the problem; that if everybody paid more attention the world would have fewer problems. And that’s simply fantasy on his part. … Kristof wants you to think that human suffering and gross inequality of human suffering should mobilize one to rectify it. If it was as easy as writing a newspaper column, raising a little consciousness, and telling people about it to right the world’s inequalities, it would have happened a long time ago. I don’t mean to sound like I think he’s being silly about this, but I think it’s a tough claim he and other activist popularizers are making—if people just knew more they’d pay attention. Well, people know what’s going on in Syria, you can’t claim that they’re failing to cover that.

His Montgomery Endowment lecture: I’ll talk about the central questions I keep wrestling with in my work. Questions of what it means to live with historical upheavals, because we all do. The limits of the activist impulse, the idea of what I think of as the humble approach to history, which is that trying to understand it deeply is a lot more rewarding, but it offers less instant gratification perhaps. The idea that you can have the right fix-it response. That we should be wary of our impulse to think the only meaningful lens to look at the traumatic history of others is, ‘That’s easy. I’ll come in there and take care of it for you.’ It’s sort of insulting to the rest of the world to think that otherwise untrained 18 and 19-year-old kids can come in and take care of all their problems for them.

These are cultures that have been around for 5,000 years and it’s not as if ours is all sorted out. The difficulty is that we’d like to come up with formulas by which we look at other people’s history that helps us understand it simply. Human rights is one of those forms. We say, ‘We’re on the side of those who are victimized by power, we are against the abuse of power. We are for democracy and against anything else. We are against secrets and lies.’ But these are all almost childish measures of really complicated political situations. So I really want to address the need for making political judgments, for thinking about political situations politically. I think we have a tendency to take that away.

So I’ll tell stories that I’m working on and address these central questions. That watching Rwanda evolve, and writing about Abu Ghraib and other places that I’ve written about, even looking at the Syria crisis where we’re suddenly confronted by a sort of unanimous understanding that something terrible is happening and who the biggest bad guys are and realizing that we’re in a bind. There’s nothing obvious to do. And there’s a very high risk that we may make things worse by anything we might do. Given America’s incredible position in the world, it’s probably more important for us to think seriously about our limits than to talk loosely about how we know what’s best and we can fix it all.

Preventing the genocide in Rwanda: The United Nations (U.N.) was in Rwanda at that time [1994], with a peacekeeping mission. The world was there. So the discussion afterwards, to some extent, has been framed as, ‘How did we fail to intervene?’ And that’s not accurate. We succeeded in pulling back. The policy wasn’t, ‘Oh, we should intervene, but we failed.’ To fail you have to try to do something. The American policy was to get out of there when the situation got out of control. That’s where the shame lay above all to me. There is real debate to be had about what could’ve been done. A lot of lives could’ve certainly been saved, even with the limited force that was already there.

You’re dealing with a mob in Rwanda and mobs are always organized, but they’re also mobs. And mobs draw their courage from their mass. If you can break up a mob, the individuals in it are much less likely to do the damage that they do as a mob. So if you’ve got a bunch of guys running down the road with machetes who are out to kill, and you’ve got armored personnel carriers with guns on them, and you’re able to shoot at them or over them, that could have a chilling effect. If you take out the radio station, which was driving the killing and was kind of a command center, broadcasting encouragement and sometimes giving very specific directions about where to find people who had just been chased out of their house by a militia group. You take that out or better yet put in a different message, a very intense message, it makes a big difference.

There are a lot of things you can do short of paving the place in U.S. Marines. But sending a signal that you’re withdrawing in front of something like this, the U.N. abandoning people who were under their immediate protection. People who had come to their compounds, by the thousands sometimes, and then withdrawing and leaving them there to be hacked to death. That’s not just failing to intervene, that’s actively being complicit in the slaughter and encouraging the killers.

So Rwanda is a very specific situation in that way, and there was a comparable case in Bosnia. To me the worst of all scenarios is not doing nothing, because if you do nothing and you send a signal that you’re not going to do anything people can at least react to that properly. It’s making a false promise of protection. That’s what we did in Rwanda, and that’s what we did in Bosnia with the safe havens in Srebrenica.

Rwanda today: Rwanda is a different place than it was in 1995 when I first went there. I went back and re-read my notes from then and at that time people were in despair that this place could ever function again as a society, much less be secure. Now it’s one of the safest places in Africa, it’s very secure, and it’s always been very organized. This is one of the aspects of the culture that made the genocide in part possible because you could organize people to a purpose. But it’s not just that. It’s an authoritarian government, but it’s very much of a nation-building government.

When you look at it from the outside, our checklist of democratic and human rights standards isn’t being met the way we’d like, but on economic development, on health care there’s been a massive public health revolution, there is now mandatory public education, and it’s illegal for children to work. So you no longer see families working in the fields the way you used to; it’s just adults. The schools are pretty bad, but the government’s attitude is like the classic revolutionary attitude: ‘We will make a massive change and then we will improve it as we go along.’ So we’ll go from something unacceptable—nobody’s in school except a few elites—to everybody’s in school. That’s much better.…

But there’s still the extraordinary condition of killers and survivors having to live side by side with levels of trauma that are limitless. It’s a completely unique situation. Rwanda really is one country and the Hutus and Tutsis are all one ethnic group. They speak the same language, worship the same god, live in the same territorial area, they intermingle, they inter-marry, one can become the other, and there’s nowhere else for them to go. There’s no Hutu-land or Tutsi-land. …

The other thing that’s so interesting is that we’re now 18 years removed; a full generation has come of age, post-genocide. Students who were born then are now in college there and here in the states. They are in some sense carrying the wounds, and you don’t know what they believe because a lot of it happens quietly at home. But they’re mixing again, intermarriage is happening again at a much higher rate than it was a decade ago. Many of them have grown up in this new ethic of ‘We’re all one nation,’ and it’s worked okay for them.

So we’re only beginning to be able to think about the big question, which is how many generations does this take? Some people say, ‘Oh, it will take a few years,’ but I don’t think we know how long it will take to be able to measure stability, which I think is fascinating. So that’s really what I’m interested in with this new book I’m working on. It’s about what it means to live with it, for them and also in a way for us. And the limitations on the intervention questions, and the limitations of our ability to fix it. The need for them to fix it.

Must-read books: A novel that I urge a lot of people to read is Man’s Fate by Andre Malraux. It’s set in the Shanghai insurrection and the characters are almost archetypal, but thoughtful, eccentric.

In terms of great works of non-fiction, I always urge people to read My Traitor’s Heart by Rian Malan. He’s a South African, a Boer who comes from an Afrikaans family that has been involved in every chapter of white South Africa and who are in some ways the squires of apartheid. And he as a young guy in the ’70s growing up in white suburban South Africa he begins realizing the outrageousness of the system that his family had thrived on. He moves to America as a journalist and becomes a Rolling Stone writer, and then goes back to South Africa during the last days of apartheid and reports on murder cases, black-white murder cases. It’s a deeply beautiful combination of memoir, reportage, grappling with one’s place in the world, and the stains you carry politically. It’s a masterpiece.

Established in 1977, Dartmouth’s Kenneth and Harle Montgomery Endowment provides for “the advancement of the academic realm of the College” in ways that enhance the educational experience, in particular that offered to undergraduate students.