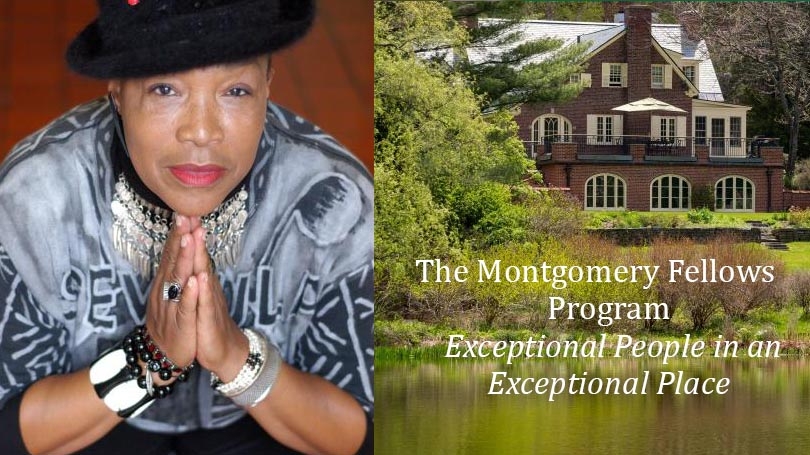

Each One, Teach One: Rhodessa Jones Inspires Storytelling

Performer, writer, and director of the Medea Project, Rhodessa Jones talked about theater and activism through community work and storytelling at a luncheon with students organized by the Montgomery Fellows Program.

Founded in 1989, Jones’ Medea Project: Theater for Incarcerated Women is designed to empower incarcerated women and women with HIV through individual storytelling and theatrical performance. She tells students that her project was founded following some intriguing experiences with people, and her own life experiences.

“I had a daughter before I became a woman,” she said. “Being a mother at 16, I was lucky to have a mother and father who were there for me. My father said, if I only have two grains of rice, you get one grain of rice and your daughter gets the other but please don’t give my blood away. I was going to give her up for adoption; for him it was like giving away his child, and he didn’t want that,” she recounted.

When she was 23 years old, Jones joined a dance company and did aerial dancing together with her daughter. “At that time, I was learning about women’s place in this world politically, and what we can do with our voice and our work.” Jones recalled an invitation to join postmodern dancer, Anna Halprin’s dance group in San Francisco. Quoting dancer Martha Graham, Jones said that people in California believe anything is possible, and soon thereafter found herself in the midst of dance and community work among women.

Another defining opportunity for Jones came through the California Arts Council when, in 1978-1979 she was asked to instruct children. On this experience, Jones remembers, “In San Francisco, you have an incredible plethora of faces and cultures, so I thought, what can I really teach these children about who they are? So, I had them bring their grandparents in a ‘show and tell’! They would be from China, Samoa, etc. and these grandparents would be thrilled that someone was interested in hearing their story! It was amazing to see the other children listening.”

With growing interest and passion for race and culture, Jones’ “Aha!” moment that catapulted her career was when she was hired to teach aerobics to incarcerated women at the San Francisco County Jail. Though at first dumbfounded by the invitation to do such work, she recalled feeling inspired as soon as she saw many brown and black women upon entering the jail facilities.

“There was a woman calling my name, and it didn’t take me long to realize this young woman went to grade school with my daughter. I held her hand and talked to her, and the jail security were probably thinking what is going on, you’re not supposed to touch people here! But this little child - she had sleepovers with my daughter at my house. And something in me said, this is it, Rho. I never looked back.”

From meeting these incarcerated women, learning individual stories from grandparents with their grandchildren, and being the only black girl dancing among white girls in San Francisco, Jones learned that we must love people and we must meet people where they’re at. Her work with women of color in jail was further empowered by asking them about their stories - getting to the heart of who they were before incarceration, and why they are in jail now. In speaking of theater and how it saved her life and provided her a stage to tell her story, Jones’ Medea Project also supports storytelling by women who were rendered speechless by various circumstances, whether through structural violence on gender and race, poverty, sexual health, or other traumatic experiences. Her shows and her writing explore drug addiction and the drug epidemic in both the United States and Africa; they explore racial, gender and sexual violence, which her work in South Africa and Nigeria has addressed in the past.

When asked about her work with incarcerated women in Africa, Jones shared a particular experience. “One woman told me that her man of five years took the baby they made together to Nigeria from South Africa to meet his family. She never saw him again. She is left with 5 boys who have had the good life of going to school but now she cannot afford the school fees. Then a ‘friend’ decides to help her. Unknowingly these women put themselves in harm’s way, and they get caught smuggling drugs. Once you get these women to talk about themselves and how they ended up where they are now, you get to the heart of their struggles,” she asserts.

Back at Dartmouth as a fellow this fall term, Jones is staying at the Montgomery House with colleague and friend, Elizabeth Spackman, to continue teaching students the power of art and sharing stories.

Jones has taught students that collective care is more important than self-care, stating that “We all have to step up and be soldiers in this scary war.” Herself moved by the African-American proverb, “Each one; Teach one” (which derives from enslaved African-Americans in the US teaching one another to read and write after being taught themselves), Jones believes that it takes a village to create progress in a deeply wounded society. Spackman added that telling your story and getting people to tell theirs does not complete the work. “It doesn’t end with the individual. It ends with creating a collective piece and even then, the work doesn’t stop,” she says, motivating students to continue storytelling, to continue talking about how we as a society can move forward and become better together.

Spackman first met and worked with Jones as a community service student at UC Berkeley, and has since collaborated with her in the Medea Project shows and script writing in San Francisco and Africa. Jones and Spackman are currently writing a handbook that chronicles her work in theater and activism, one that can be a resource for both performers and activists in finding meaning and inspiration through community engagement. Together at Dartmouth they will be giving talks to students about their work, activism with race, gender, and HIV, and using theater for social change.

Jones was soon joined by award winning rapper and artist Che ‘Rhymefest’ Smith, another fellow this fall term, to continue the conversation about art as the foremost frontier in social change. Visit the Montgomery Fellows Program website for updates on all Fellows and upcoming events.

For more information on the Medea Project, visit the project website.